Let’s say that you have front-row tickets for the Toronto Raptors.

Your tickets are in “Row 1,” which is the front row, but the tickets themselves don’t say “front row” anywhere.

This is the seventh year that you’ve had these tickets, and you’ve always enjoyed coming to the game, sitting in the front row, and stretching your legs out like nobody else in the arena can.

But now, let’s say that you show up for a game and there are two new rows in front of you.

Suddenly, you’re in “Row 3.”

Except you’re not actually in Row 3; you’re just in the third row.

Your seats are still in Row 1, as they always have been.

But now, there’s a “Row B” in front of you, and a “Row A” in front of it.

While this is obviously a fictional account, it has been known to happen in sports stadiums across North America. You might suggest that this “simply can’t happen” or that it’s “unfair,” but somewhere in the season ticket holder’s agreement, there will be verbiage that allows this.

If you were the person who was just screwed over, you might say, “Forget this, I’m giving up my tickets.” But in a hot ticket market, there could be fifty people lined up behind you to take your “Row 1” seats that are in the third row. And if the market for the sport, the team, and the tickets happened to be ice-old, maybe there would be verbiage in the agreement that wouldn’t allow you to get out of it.

I’m going to draw a parallel here today to how pre-construction condominiums are designed, marketed, altered, and sold in Toronto, and have been for the last two decades or more.

I receive a lot of emails from the TRB readers, many of which contain questions about current events in the real estate market, media articles, and suggestions for future blog posts.

Case in point: the blog I wrote three weeks ago about an “unsellable” condo floor plan was the direct result of an email from a TRB reader; otherwise, I’d have never seen it or considered writing about it! This is one of the reasons why I’ve always considered TRB to be, at least in part, a collaborative effort among myself and the readers; a community of sorts.

Sometimes, I’ll receive the same newspaper article from two or three readers, often suggesting, “You gotta write about this!”

Then other times, I’ll receive an idea or an article from a slew of people! That was the case two weeks ago when no fewer than six people emailed me this:

“She Says She Bought A Two-Bedroom Townhouse, They Built A One Bedroom Plus Den. Here’s Why She’s Never Going To Buy Pre-Construction Again”

The Toronto Star

January 17, 2026

My colleague, Chris Cansick, told me over that weekend, “You gotta read this article in the Star about pre-construction. It’d be perfect for the blog.”

On the Monday that followed, I heard this from two other colleagues at the office as well.

The content of the article is nothing new, or at least it shouldn’t be.

If you’ve been reading Toronto Realty Blog for longer than a year or two, you’d have heard us talk about this countless times.

The problem we’re going to discuss today is simple:

Developers can change anything in the building or the unit that they want. It’s up to the buyers to argue that the change is “material” and seek remedies and/or compensation.

Let’s have a look at an excerpt from the article:

Instead of popping the champagne, Yvonne Tsui was panicking.

Seven years after she put a deposit down on a Victoria Park Avenue townhome, between Eglinton and Lawrence avenues, it was finally finished.

But when she got the keys in 2024, her first home was not what she had dreamed of.

Instead of the two bedroom she said it was marketed as — which the developer disputes — she arrived to find a one bedroom, plus a doorless den.

The closing took months, forcing her to pay thousands of dollars in occupancy fees, and condo fees were 50 per cent higher than initially marketed.

“I have been robbed of the joy and excitement one should feel as a first-time homebuyer,” she said.

Experts and buyers say the case is a warning for purchasers of pre-construction units.

Nothing new, right?

Seven years to complete a condo, uh-huh.

“Developer disputes,” of course.

Higher condo fees, check.

Disappointment, for sure.

This is all exceptionally common in the pre-construction condominium industry, and it’s among one of the many, many reasons why I have never sold a pre-construction condo, but also why I have spent two decades warning buyers with stories like this.

The article above says “Experts and buyers say the case is a warning for purchasers of pre-construction units.” Sure. But how many of them were offering these warnings seven years ago when this individual purchased? Very few, I suspect. In fact, these “warnings” are quite new for post pundits, commentators, advisors, and “experts,” and only began to be commonplace after the pre-construction condo market fell flat.

But if you’re a long-time reader of TRB, you’ve known about this for at least sixteen years.

November 1st, 2010, I wrote: “Material Changes”

Well, the title of the blog post wasn’t that original or inventive, but the content sixteen years ago certainly was!

While I had written about material changes in the pre-construction condo world many times on TRB, this was the very first dedicated post I had written.

That was sixteen years ago.

There have been all kinds of time for buyers to learn about what developers do, on the regular, in between selling pre-construction condos and actually building them.

More from the article:

Tsui’s contract appears to state that both the square footage and the dimensions are “approximate” and may differ from what was shown in marketing materials.

She provided the Star with a screenshot of the condo fees from marketing materials, listed as $0.24 per square foot. But they turned out to be $0.36.

Tsui also said the monthly fees for hot water heater rental are unreasonably high, and over the term of the contract add up to more than the stated value of the heater, according to the rental agreement, a cost she says wasn’t disclosed when she agreed to purchase the home.

Water was also supposed to be included, but has turned out to be extra, she added.

Is it possible that the buyer never read her agreement?

Probable. Not “possible,” but probable.

Nobody reads these agreements, of course. They’re quite lengthy! Many years ago, I did a YouTube video (that didn’t age well, so I shudder to share it…) where I read out all sorts of clauses that used verbiage like “subject to change,” and that’s exactly why this buyer, and everybody like her, has absolutely, positively, no leg to stand on.

Okay, fine, I’ll share it.

November 29th, 2017:

Could somebody have told me to invest in a lav mic back then? Geez. This was almost “Blair Witch Project” territory, but I digress…

The point is: developer contracts are full of verbiage that allows them to change, alter, substitute, revise, modify, amend, or at times even cancel or remove features, finishes, or other elements of both the unit in question or the condominium itself.

Now, if you think the above article – about the two-bedroom being a “one-plus-den” is bad, check out the next one…

“When The Penthouse You Bought Is No Longer A Penthouse. Plan Changes Go To Court”

Toronto Star

January 26, 2026

Now do you see why I made the analogy about “Row 1” versus “Row A” in the introduction of today’s blog post?

From the article:

Imagine buying a pre-construction penthouse only to find out that the builder decided to add another floor on top of the building, and you are now getting a sub-penthouse.

That’s what happened to Chirag and Priyankaben Trivedi when they agreed to purchase a condominium to be built on Kalar Rd., in Niagara Falls, Ont.

Around the time they signed the purchase agreement in 2022, the builder — a numbered company operating as Urbane Communities — provided the Trivedis with a disclosure statement as required under the Condominium Act.

The plans showed the unit, suite 316, on the third floor, which was the top floor of the building.

Just shy of two years later, Urbane delivered a revised disclosure statement to the Trivedis by email.

Among other things, the statement informed the buyers that the development would now include a fourth floor. The letter accompanying the statement informed the buyers that the change would not affect the location of their unit.

Okay, okay, so maybe this isn’t as big a deal as I made it out to be!

I mean, we think of a “Penthouse,” and we think the 58th floor, right?

This story would clearly be a lot more interesting if it involved a $6,000,000 penthouse on the 58th floor of a building, whereby the builder then added a 59th and 60th floor, but you get the point.

It shouldn’t really matter in the context of today’s discussion, though.

Just as you wouldn’t expect the Toronto Raptors to add “Row A” ahead of your “Row 1” seats, you wouldn’t expect a developer to add a 59th floor above your “Penthouse” on the 58th floor, nor would you expect them to add a 4th floor above your penthouse on the 3rd floor.

So what happens in a case where there’s a material change?

Well, first you have to define “material change.” This is the problem!

A condo buyer will have a very different definition of what’s “material” than the developer will, and that’s why it always ends up in court.

For example, if a buyer contracted to purchase a condominium with one type of floor tile but a different one, of similar quality, was substituted, would that constitute a material change?

I doubt it.

And the buyer would have an exceptionally hard time proving it was, or that any remedy was needed.

But what if a buyer purchased a condo with a Bosch kitchen appliance package and arrived at the condo for the pre-delivery inspection to find an Amana kitchen appliance package? Would that constitute a “material change?”

You will probably say, “Yes, that’s a difference of several thousand dollars!”

But a developer is simply going to say that they don’t “view” this as a material change, and thus the onus is on the buyer to seek restitution.

Now, what if there was a major change to the floor plan that significantly impacted the way you could use the space?

The square footage wasn’t changed.

The room sizes weren’t changed.

But there was a large concrete pillar added in the building design and it was placed right in the middle of the living room!

Would that constitute a material change?

Or what if it was an HVAC system that, instead of being placed in the corner of the room, or next to a closet, was right in the middle of the living space, thereby completely killing the flow, design, and functionality of the space?

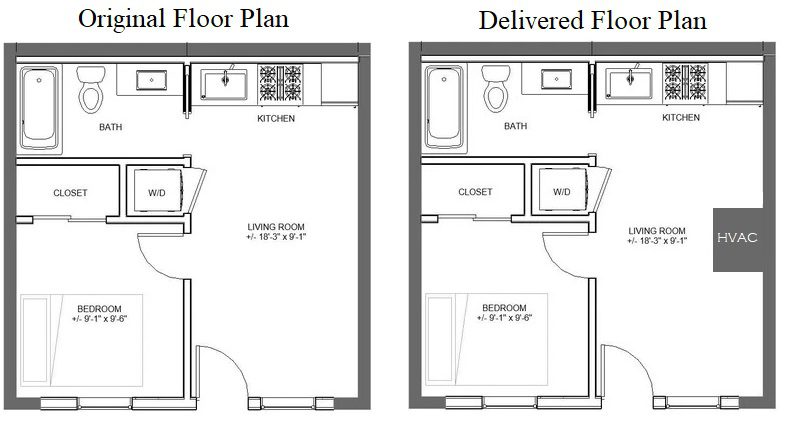

Let me draw up a quick example:

If you were a buyer who purchased a condo and attached the floor plan on the left to your Agreement of Purchase & Sale, and when you took possession of the unit six years later, found that you had received the floor plan on the right, would you feel that this constituted a “material change?”

This happened to a client of mine way back in 2007 or 2008.

He bought through the developer in pre-construction (not through me) and he hired me to sell the condo on the resale market, and this is precisely what he experienced.

He went ballistic, and rightfully so.

He had purchased a dining room table and a sectional couch specifically to fit the floor plan on the left, only to find that the developer had placed a massive vent stack right in the middle of the floor plan.

Of course, he went to his lawyer, but nothing happened.

The onus would have been on him to litigate against the developer and prove that the change was material and affected the value of the condo, but that would have taken time and cost money.

This is why the developer always wins.

Er, I mean, almost always wins.

What happened in the case of the “penthouse” condo as described in the Toronto Star article above?

From the article:

After reviewing the evidence, the judge decided that the addition of a penthouse floor was objectively material to the Trivedis, and it is likely that they would not have purchased the unit if they knew it would be on the floor below the penthouse.

The judge wrote, “For these reasons, I find that the addition of a fourth floor to the condominium development, in this case, is a material change.”

Amazing!

So they won, right?

Ummm…….about that….

This conclusion meant that the buyers only had 10 days after receiving the revised disclosure statement to either terminate the agreement or apply to a judge for a determination. The negotiations between the lawyers did not extend the buyer’s 10-day window.

Since the Trivedis failed to exercise their right to terminate the contract within the 10-day period, the contract was still binding and they were not entitled to terminate it.

The Trivedis were ordered to pay the builder’s costs of $25,000.

So even though they won, they ended up losing.

It’s a simple case of “David versus Goliath.”

The developers are far more experienced, have deeper pockets, more resources, better lawyers, and their standard contracts are iron-clad.

For any buyer to “assume” anything is exceptionally naive and misguided.

This isn’t about right and wrong; it’s about reality.

So let me end with this exceptionally cynical piece of advice:

If you’re a pre-construction buyer, which you absolutely should not be, you must assume that anything and everything in the unit you’re buying, and the condominium in which it’s located, could be subject to change, regardless of impact, value, or “fairness.”

To assume otherwise is to assume that a band-aid can fix a crack in the pavement…