Raise your hand if you know the difference between a “foreclosure” and a “power of sale.”

For the record, my palm is open and my hand is aligned with my body, but my elbow is bent and my hand remains about shoulder-height…

Do I know the difference?

Yes. More or less.

But do I know the legal nuances of both, and can I speak to the borrower and lender’s respective rights, pros, and cons?

Not necessarily.

What I do know is that, in 2025, lenders are using the “power of sale” method to recoup their loans far more often than actually foreclosing on the property and selling it thereafter.

The biggest difference between a power of sale and a foreclosure can be summed up as follows:

The courts are involved in a foreclosure. The courts are not involved with a power of sale.

As a result, almost every lender (especially the major banks) will include a power of sale provision in their standard lending agreement, which about 0.0001% of borrowers would actually read, absorb, and understand.

As I said, I can’t really explain the process of each method, but I would be remiss if I didn’t mention one more difference, which, some of you may think, is more important than the first:

The borrower loses all equity in the property after a foreclosure, and any associated rights. The borrower may retain some equaity in the property if the sale proceeds, after expenses, exceed the debt owed with a power of sale.

So if the power of sale is faster, easier, less costly, done outside the courts, and the borrower can retain equity if the sale proceeds exceed the debt owed, then everybody wins, right?

Last week, I was perusing MLS and I saw a fourplex for sale in the west end on a fantastic street, but when I looked at the “Seller” field, I was surprised to see that it was a lender.

Not a Big-5 bank, but rather a second-tier lender that most of you would have heard of.

I was curious, so I looked up the property in Land Registry and found the owner: a former real estate agent.

How’s that for coming full circle? The cynics are going to love this…

The property was for sale for over $2,000,000, but the owner purchased the property in 1987 for $280,000.

What in the world did he do in order to lose his rights?

Did he leverage the property to buy others?

Did he use the property as an ATM?

Who knows.

But the very next day, I was searching for condos under $450,000 (yes, I’m planning to buy another condo for long-term investment…) and one really jumped out at me!

When I see a condo that’s listed for sale for a price that seems “too good to be true,” the first thing I do is scroll down to the REMARKS FOR BROKERAGES and look to see if there’s any nonsesne about “offer dates.” As I’ve said before, an offer date on a condo, in this market, is a farce. We’ve covered this time and time again on TRB, looking at listings where the seller and listing agent have decided that after their fourth attempt to sell the property, they should price the property super-low and set an offer date.

It doesn’t work.

In any event, this particular property said nothing about an offer date.

So then I went to look at who’s selling the property, and wouldn’t you know it, the seller is a lender.

I won’t say which one, but I will say that this listing fascinates me!

Asking how a power of sale comes to be, or why, is a great question.

Today, I want to take a deep dive into the listing history and see how we got “here.”

This building was registered as a condominium corporation in December of 2020.

The transfer amount shows as just over $350,000, which is the price paid for the property, net of HST, so the actual purchase price was likely closer to $400,000.

With land transfer tax and other closing costs, the original buyer might be in for, say, $425,000.

The first time the property appears on MLS is in December of 2021 when it was listed for lease for $2,100.

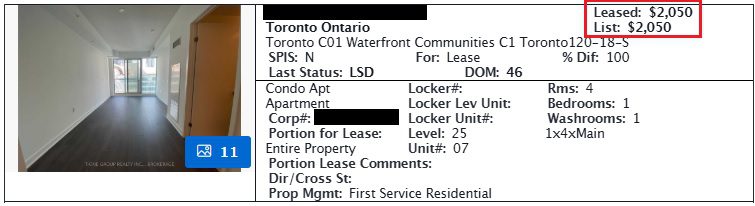

The price was decreased to $2,050 in January of 2022, and the property was subsequently leased:

In November of 2022, the property was listed for lease.

The dates line up to signify that the tenant who took possession in January of 2022 provided the required 60 days’ notice for vacancy at the end of the one-year lease.

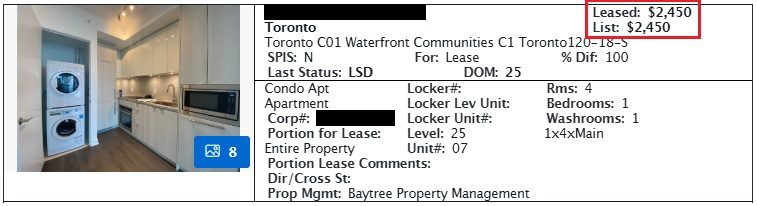

Only this time, the price was a wee bit different.

No longer $2,050 per month! The market had changed!

The property was leased in December of 2022 for an early-2023 vacancy.

According to Land Registry, the property was sold privately in August of 2023 for $660,000.

Not a bad payday for the original buyer!

Given the condo “closed” in 2020, I would estimate the original purchase in pre-construction to be somewhere around 2014. Nine years later, the $400,000’ish purchase price versus the $660,000 sale price shows an excellent return!

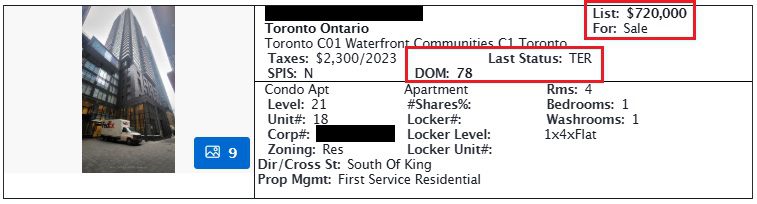

On January 31st, 2024, the new owner listed the property for sale for $720,000:

The listing remained up for 78 days before it was terminated.

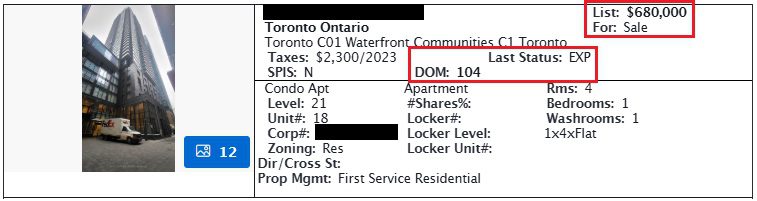

On April 18th, 2024, the property was re-listed for $680,000:

This listing remained up for 104 days before it expired on August 1st, 2024:

The next listing wouldn’t take place until November 5th, 2024.

Why?

What happened?

Why did it take so long for the next listing to appear on MLS, and what happened in those three months?

Well, the next screenshot will either explain things or make them more confusing:

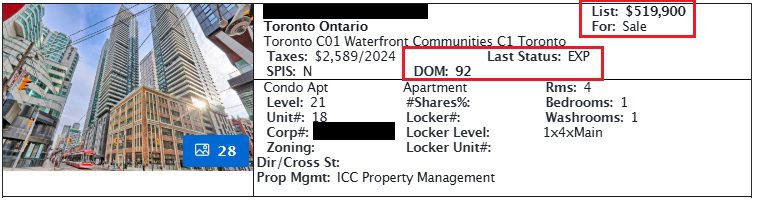

This is the next listing in the queue.

The property was re-listed on November 5th, 2024 for $539,900.

The price was reduced to $524,900 on December 6th, 2024.

The price was reduced again to $519,900 on January 7th, 2025, and that is the price which you’re seeing in the above screenshot.

So why did the owner go from $680,000 in August to $539,000 in November?

Simple.

The lender enacted a power of sale.

Let’s call them “ABC Bank.”

At some point between the expiry of the seller’s listing on August 1st, 2024, and the subsequent listing on November 5th, 2024, ABC Bank was able to force a sale. Who knows why, but we’ll assume that the borrower breached their covenant, and the loan agreement allowed for the power of sale accordingly.

The listing you see above expired on February 6th, 2025, after 92 total days on market at $539,900, $524,900, and finally $519,900.

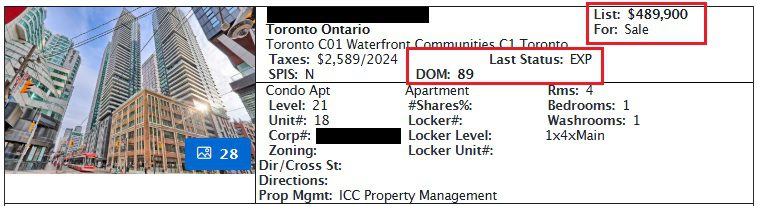

On February 6th, 2025, the property was re-listed for $509,900:

The reason you see a price of $489,900 is that, after listing for $509,900 on February 6th, 2025, the price was reduced as follows:

-$499,900 on March 6th, 2025

-$489,900 on April 4th, 2025

The listing expired on May 7th, 2025.

Later that magical day, on May 7th, 2025, the property was re-listed for $479,900:

Again, the reason that you see a price of $464,900 is because the price was reduced as follows:

-$469,900 on June 6th, 2025

-$464,900 on July 8th, 2025

Notice a pattern?

There’s a reduction essentially every 30 days.

That listing expired on August 8th, 2025.

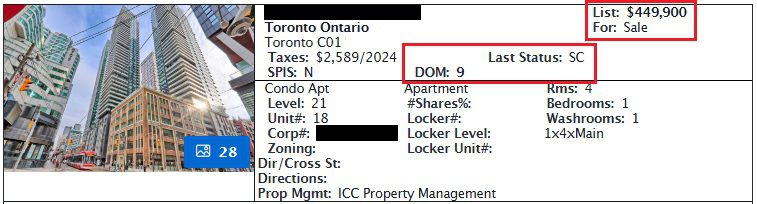

And of course, also on August 8th, 2025, the property was re-listed as follows:

What a steal at $449,900!

And that’s not sarcasm, folks. Because if you saw the “SC” like I did, you’ll notice that this unit is now sold conditionally

What a journey.

ABC Bank first listed the property for sale on November 5th, 2024, and they achieved a sale on August 13th, 2025.

Nine months, four listings, and the following listing prices:

-$539,900

-$524,900

-$519,900

-$509,900

-$499,900

-$489,900

-$479,900

-$469,900

-$464,900

-$449,900

Like I said, the listing history is fascinating!

Now, at this juncture, you likely have two questions:

1) What did the property sell for?

2) What is the property worth?

We can’t answer the first question, since the sale price will only be released if/when the deal firms up.

But as for the second question, perhaps some background on the property itself is prudent.

This is a 1-bedroom, 1-bathroom unit, and is 525 square feet according to the floor plan.

The identical layout has sold twice so far in 2025:

$445,000 – May, 2025

$456,500 – June, 2025

The difference between those two units was the level of the respective suites, as the unit that sold for $456,500 was seventeen floors higher.

Armed with this information, doesn’t the last sale price for the power-of-sale unit make sense?

It was listed last week for $449,900 and subsequently sold.

It would seem to me that ABC Bank had significantly overpriced the unit, or chased the market downward after pricing too high at the onset.

Is it possible that lenders are just as wilfully ignorant and entitled as other Average Joe condo sellers? Or was this a process they had to adhere to from the get-go in November of 2024?

Then the next obvious question becomes: could they have sold the condo for more back in November of 2024 than they did in August of 2025?

Likely, but that’s hindsight talking.

The condo wasn’t “worth” $539,900 when ABC Bank listed in November of 2024, but they very likely could have done better than the $440-$449K that they sold for last week.

I mentioned at the onset that unlike with a foreclosure, the borrower who’s property is sold via power of sale is entitled to any equity left after the sale.

The owner of this property paid $660,000 for the unit.

The property likely sold for just under the $449,900 list price.

Assuming the borrower made a 20% down payment on the $660,000 purchase price, that would mean ABC Bank advanced $528,000 for the mortgage.

So the borrower isn’t coming out of this with anything, unless he or she made a 40% down payment, which is highly unlikely.

In any event, the owner/borrower loses and ABC Bank loses.

The only person who really “wins” here is the buyer who picked this thing up for a pittance.

I know, I know, define “pittance,” and tell me your thoughts on the trajectory of the Toronto condo market while you’re at it, but I digress…

For those that simply can’t get enough of conversations about foreclosures or power of sales, I’ve covered this twice in the past two years.

First:

October 10th, 2023: “So You Want To Purchase A Power Of Sale, Do You?”

In this blog post, I went through all the clauses and conditions that you’d expect to find in a typical Schedule attached to the listing, and asked the obvious question: “Who would actually want to bind themself to this?”

Then there’s this post from last year:

November 11th, 2024: “What Does A ‘Power Of Sale’ Listing Look Like?

Similar to the example I just provided, in this blog post, we looked at a freehold property that went through the power of sale process as well.

Happy Monday, folks!

Serge

at 9:53 am

Listing history is fascinating in that it looks like a straightforward business sale approach, not realtors’ stratagemas, like $1,000,000,000, $1, $400,000, $800,000. etc. as it was described here many times.

In future, I guess, AI relator-bots will be discerning human realtors and businessmen by this.

Appraiser

at 8:18 am

To cover their bases legally, lenders usually obtain two independent appraisal reports of the subject property before listing it for sale on MLS.

The lender is also required to allow sufficient market exposure time for the property in order to display all efforts to obtain market value.

In general lenders despise taking properties back and most are not very good at it, given the varied costs and legal restraints involved.

Derek

at 11:18 am

David, maybe, for no particular reason, you can do a post explaining how the banking at a large brokerage works. What transactions on what deals results in what monies deposited into what accounts. How long is the money typically in the accounts and in what circumstances is the money transferred out, and where does it go…. What explanations could there be for money going somewhere else before going where it is supposed to go?

Appraiser

at 9:43 pm

As a former broker of record I can relay that the two owners of a certain brokerage that you refer to for no particular reason are in deep shit. I fully expect criminal charges to be laid. Trust accounts are sacrosanct – but fully accessible to fraud.

The trust account holds consumer deposit monies until the closing date of each transaction, when it is released to the lawyers as part of the purchase price and or to the realtors involved as commissions owed. The only other ways to legally move money from a real estate trust account are by court order or a mutual release.

Derek

at 11:48 am

So, not supposed to use trust funds “to repay investors in the brokerage owner’s separate holding company and to cover operational costs”?

Do you imagine that they could get away with using the trust money while there were always new sales coming in next month, but with a long period of low sales volume, they got stuck?

David Fleming

at 8:52 pm

I was asked by two different reporters to comment on the iPro Realty situation.

I’ve been asked by about a dozen blog readers to write about it.

I can’t really write about what I don’t know, but I will say – this is going to be a massive story.

https://www.thestar.com/real-estate/real-estate-leaders-call-for-immediate-police-investigation-of-ipro-realty/

https://www.theglobeandmail.com/business/article-ontario-regulator-shuts-down-real-estate-brokerage-firm-ipro/

Derek

at 11:17 pm

Yeah, I was just thinking you could explain how the banking normally works as background to the news, but looks like Appraiser covered it for us.

David Fleming

at 9:57 pm

@ Derek

Sorry, just saw this comment!

Might be too late as I’m not sure if you’re checking responses, however…

I have three brokerage accounts:

-General

-Trust

-Commission Trust

The general account is for operating expenses.

The trust account contains the money used as deposits for listings.

The commission trust account is for money to be paid out to cooperating brokerages.

The only way we can remove money from the ‘trust account’ is when a sale closes, a court order is received, or where there’s a mutual release. That’s the only legal way. In reality, I could transfer money through EFT, write cheques, or probably withdraw cash. I wouln’t though.

Would others?

Would other brokers use this money for things it’s not supposed to be used for?

For example, and this is completely hypoethetical, but would a broker who has a cash shortfall to pay operating expenses, transfer trust monies to the general account?

I would hate to think so…

estate agents in Dagenham

at 8:32 am

Really interesting read! I didn’t realize how much the power of sale process has changed going into 2025. It’s good to know that lenders are leaning more toward this option instead of full foreclosures. Definitely a reminder for buyers to stay cautious, just because it’s a power of sale doesn’t always mean it’s a great deal.